By Nina de Paula Hanika

Drawing inspiration from Surrealist Exquisite Corpses, you will explore the human figure through drawings, collages and assembled figures. Then, you’ll practice composition, and notice the shared forms across human and non-human ‘bodies’

Don’t forget to submit pictures of your work or post online and tag @natsatclub and @uolartsoutreach

Materials needed

- Newspaper/Magazines

- Scissors

- Paper

- Glue stick

- push-pins / tacks (if available)

Activity part one – Exquisite Corpses

An Exquisite Corpse is a collaborative method of drawing or writing favoured by the Surrealists. It was invented in 1925 in Paris by the surrealists Yves Tanguy, Jacques Prévert, André Breton and Marcel Duchamp.

Using a folded sheet of paper, each participant adds their contribution before passing it to someone for the next addition. When using words, the result is a collectively written poem, and the favoured method when drawing is to split a human figure into sections, with the head, shoulders and arms, torso, legs, and feet drawn separately.

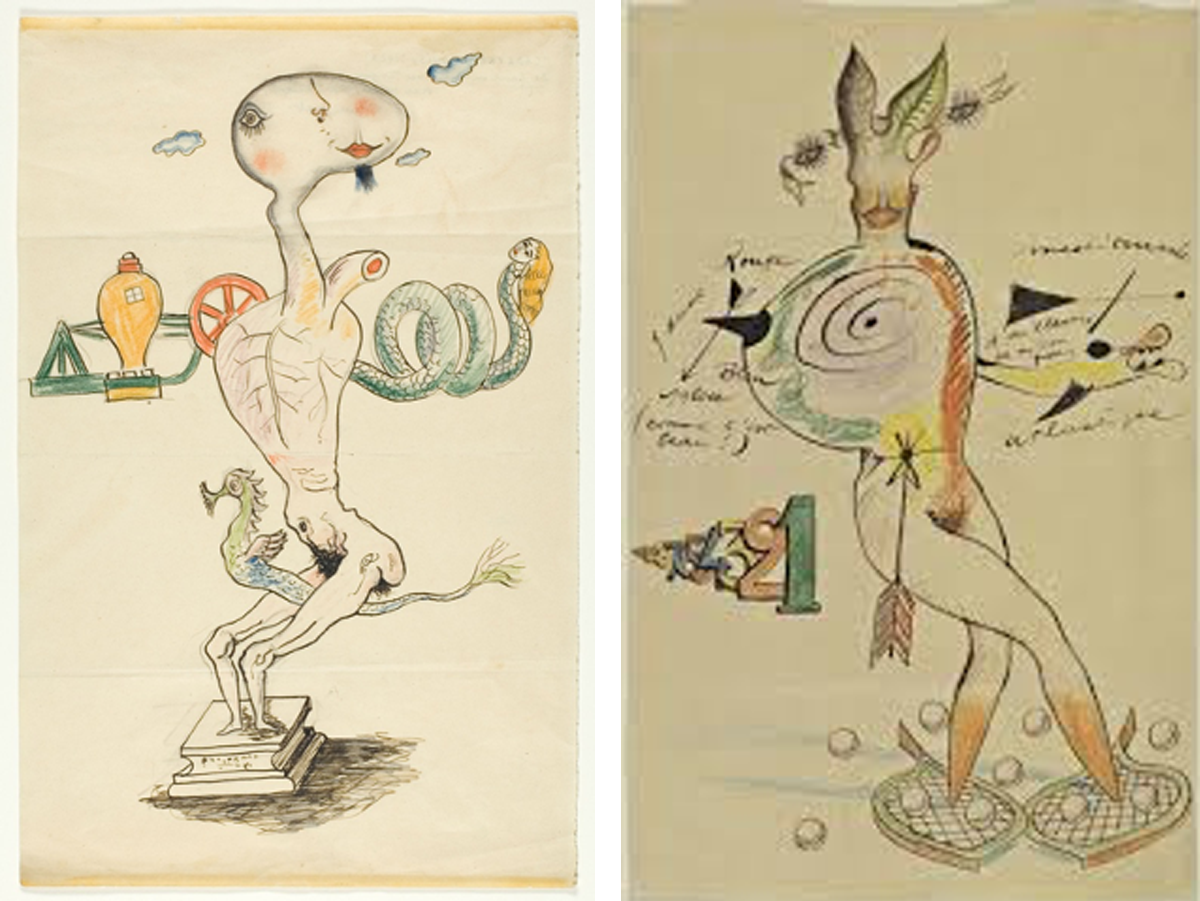

Left: Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky), André Breton, Yves Tanguy, and Max Morise, Exquisite Corpse, 1928. © 2018 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago. (Found here)

Right: Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró, Max Morise, Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky), Nude, 1926–27 (Found here)

Rather than drawing a human figure ‘from life’, the Surrealists favoured incorporating strange, dream-like, or intuitive forms into their drawings. Sometimes, like in the example above, they would exchange elements of the human body for inanimate objects, such as the feet for tennis rackets. Once unfolded, the resulting drawing creates a ‘human form’ out of juxtaposed and surprising elements, incorporating the element of artistic ‘chance’ that was crucial to Surrealism as a movement.

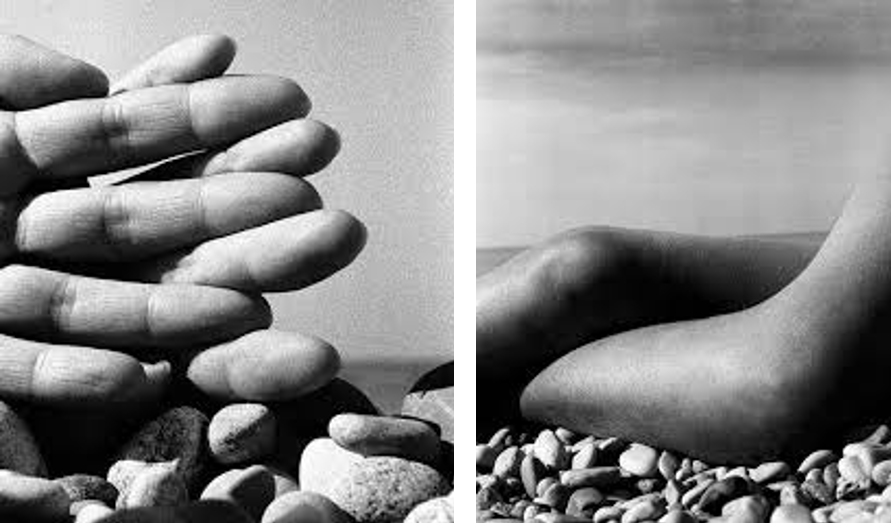

Lots of artists have produced interesting work by thinking about the overlap or relationship between the human and the non-human body. Look at the way these photographs by Bill Brandt make hands and legs on a beach look like pebbles.

Left: Bill Brandt, Hands on the Beach, 1959

Right: Bill Brandt, Nude as Landscape, (Both found here)

Or what about this photograph, taken by Claude Cahun, of driftwood and other objects on a beach? It can be really easy to make a body look like something else, and vice versa, if you change its framing, context and placement.

Claude Cahun, Le Père, 1932, Gelatin silver print, 23.6 x 17.7 cm, LAC (Found here)

Now it’s your turn – activity part one:

- Take a sheet of A4 paper and fold in half. Unfold, and fold each half to the centre-fold. Unfold again. The sheet should now have creases dividing the page into four sections.

- Drawing with a partner, the first participant should draw a head in the top section. Try to be as free and imaginative with this as possible, incorporating whatever shapes, forms or elements come to mind. It does not have to be ‘realistic’!

- Once finished, fold the section backwards so the drawing is not visible, but leave two marks overlapping the fold so your partner knows where to join their drawing to. Pass to your partner, who should draw their ‘shoulders and arms’.

- Repeat Steps 2 + 3 with ‘hips and thighs’ and ‘shins and feet’ in the following sections.

- Unfold your drawing and marvel at your collaborative Surrealist creation!

Reflection:

- How did you decide to draw your different body parts? What choices were you making? What were you imagining during the process?

- How different were your parts of the drawing from your partner’s?

- How ‘conscious’ or ‘subconscious’ did you feel your forms were?

- Did you include any objects, or non-human elements, in your ‘exquisite corpse’?

Find out more about Exquisite Corpses here

Activity part two – Push-Pin Figures

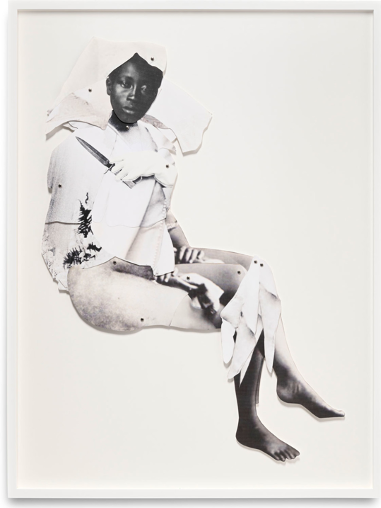

Frida Orupabo is a sociologist and artist living and working in Oslo, Norway. Her work consists of digital and physical collages in various forms, which explore questions related to race, objectification, family relations, gender, sexuality, and identity.

She produces collage works which break apart and reassemble the human figure, joining each part together with push-pins. The final works have the appearance of unsettling paper dolls.

Frida Orupabo, Keeping It Together I, 2016-2017 © Frida Orupabo (Found here)

Warm up – body part brainstorm:

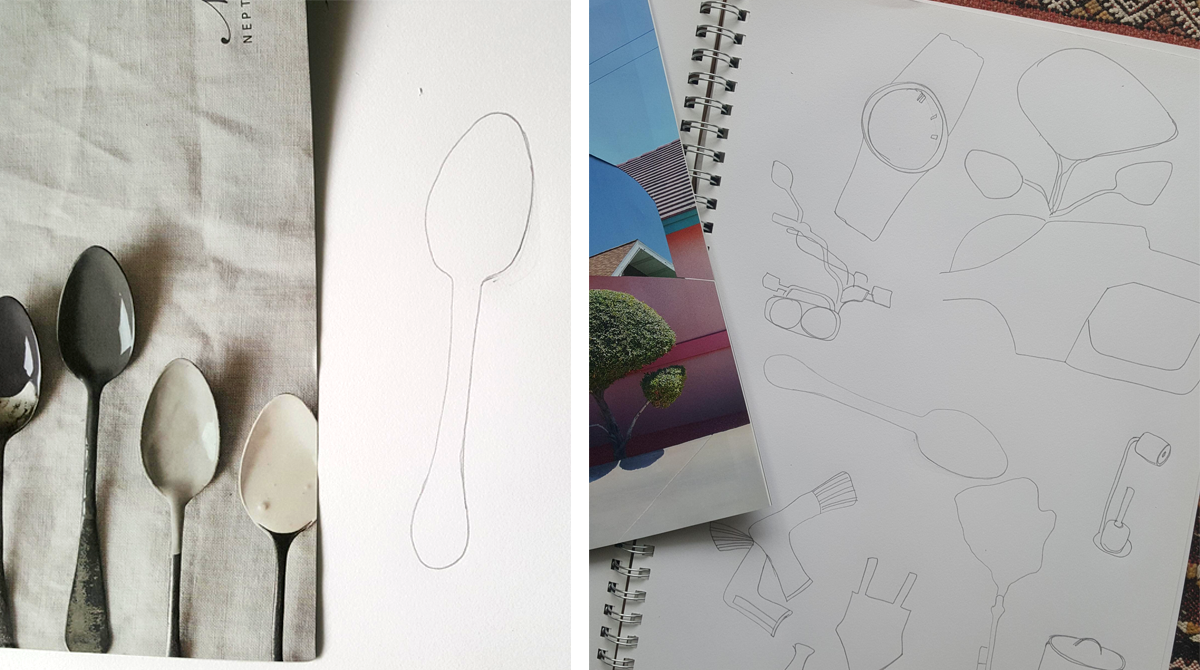

1. Using magazines and newspapers, look through all the images you can find. Can you see ‘human forms’ in images of non-human things?

2. Draw these forms as simple outlined shapes. Don’t think too much about this – just draw lots of quick sketches of as many things as you can!

Reflection: Look at all your sketches. If you were going to make each one a body part, which part of the body would they be?

Push-pin method:

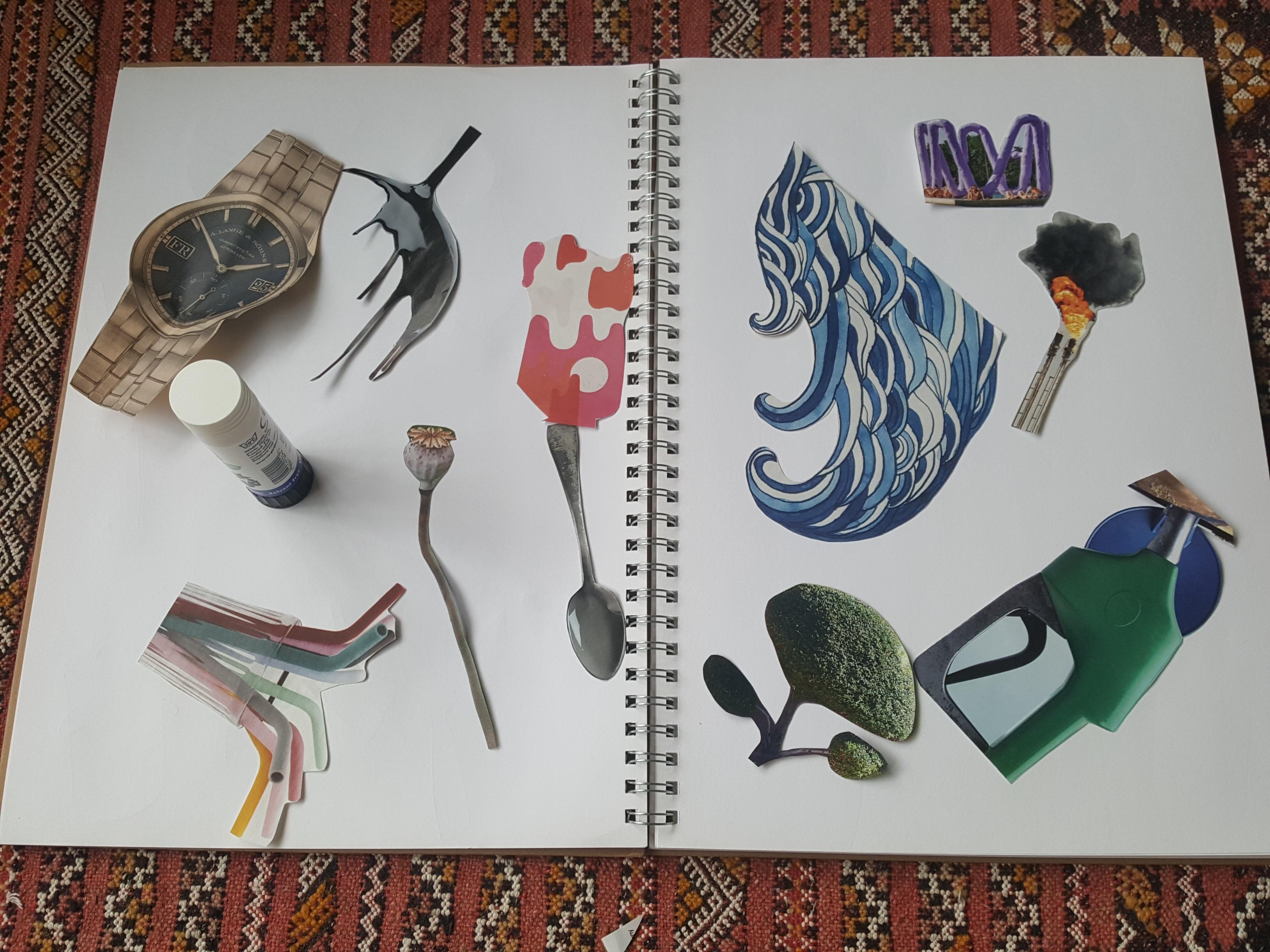

Go back to the magazine/newspaper images you drew in the warm-up exercises.

Think about the sketches you made and which ones you thought would make the best ‘body parts’. Cut these images out from the magazines and stick with Pritt stick onto paper. Cut out shapes again (this is just to make them a bit stiffer).

Using a piece of paper as a base, arrange your ‘body parts’ into a ‘figure’. Experiment with turning them around, rearranging them and seeing where they look best. Use pins (if available) to pin parts together and stick them to the base paper.

Continue doing this until you’ve pieced together an entire ‘figure’ !

Reflection:

- How difficult was it to make a human ‘figure’ out of non-human ‘things’?

- What kind of ‘things’ did you like using best?

- Has the way you look at shapes and form changed? In what way?

Thank you for taking part in the University of Leeds Art&Design Saturday Club Workshop.

Submit pictures of your work or post online and tag @natsatclub and @uolartsoutreach

Contributed by Nina de Paula Hanika, University of Leeds Art&Design Saturday Club

Nina is an Education Outreach Fellow working with the Saturday Club at the University of Leeds. She is an MA student in the Social History of Art at the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies, and gained a BA in the History of Art from Cambridge University.

She has previously worked at visual arts organisations including The Hepworth Wakefield and for arts communications agency Rees & Co PR. She is passionate about social justice, arts accessibility, and what the visual arts can teach us about ourselves and others.